Your organization has a unique culture shaped by shared values, assumptions, and beliefs as to the best and right way to do things to be successful. Over time, this tacit belief system becomes embedded in all aspects of organizational life. The challenge is this very tacitness makes it difficult for people to articulate why things happen the way they do. While this is fine when times are stable and the organization is successful, it can become a problem when you are in a dynamic environment facing significant internal and external change. How do you know if your culture is helping or getting in the way of your strategy, mission, and goals? How do you know what needs to be protected and changed?

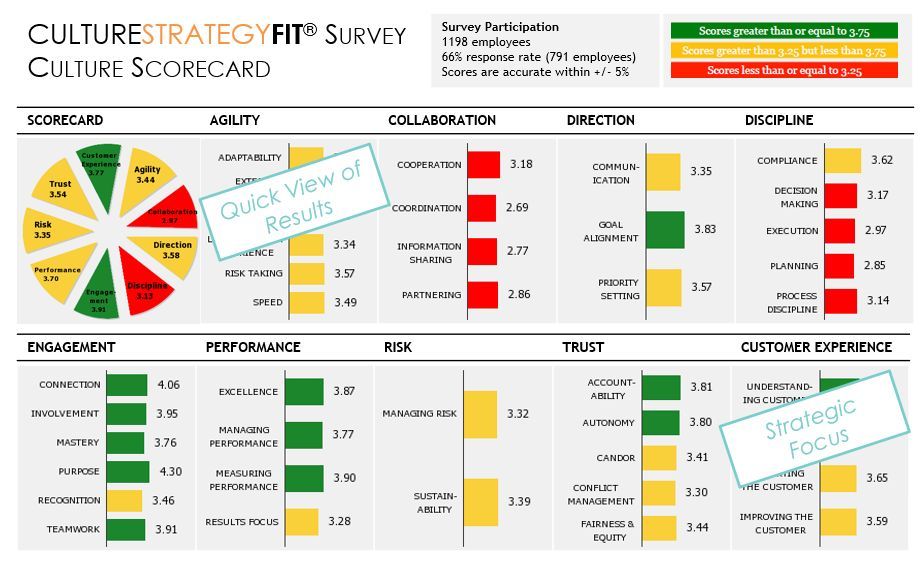

The CULTURESTRATEGYFIT® suite of Culture Surveys are research-based, globally appropriate and ready to help you better understand your culture, set priorities for action, and measure progress. They are unique in that each survey is designed for a specific purpose and context. They are special in that they tell a story rather than simply provide data. They reveal the insights leaders need to intentionally shape and change culture.