When Culture Eats Strategy

I am excited about my new book which is available from Amazon on February 20th, 2024. I have included chapter 5 of this book for my LinkedIn community and for all leaders, HR, and OD practitioners. I hope you enjoy it.

In chapter one, I stated that organizational cultures aren’t good or bad, instead, they exist for a reason. The problem is that sometimes things change and the culture that served the company so well in the past starts interfering with its ability to achieve its goals. The story of AVSC and how its risk-averse culture impeded revenue growth is just one of the many examples I’ve encountered over the years. When this happens, the company’s culture is no longer an asset; it is a problem that needs to be solved.

A Disconnect Between Strategy and Culture

The situation AVSC faced was not unusual. Companies, regardless of their industry, location, or size, must adapt their strategies to remain competitive and achieve their goals. The challenge is that no matter how great your company’s strategy is, it will fail unless the culture supports it. If this alignment of culture and strategy is weak or missing, the culture becomes an anchor weighing down the company’s efforts to execute its strategy, creating culture drag.

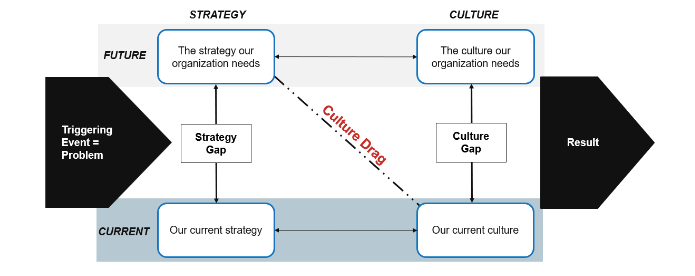

Diagram 5: Culture-strategy alignment and the effect of culture drag on strategy executionappens, the company’s culture is no longer an asset; it is a problem that needs to be solved.

Diagram 5 illustrates the effect of culture drag on strategy execution. When culture and strategy are aligned, all aspects of the organization work together to support strategy execution. Assuming the strategy is the correct one and is well executed, this alignment of culture and strategy helps the company achieve the outcomes it needs.

When this happens, shareholders are happy, the BOD is happy, market analysts are happy, customers and suppliers are happy, and leaders and employees are happy. Then something significant happens, a triggering event, and we have a problem: the company’s strategy is no longer achieving its financial targets and goals. Performance declines, creating pressure to do something different. When this happens, the company experiences a strategy gap, which is the difference between the current strategy and the strategy the company needs to achieve its goals. If the company does nothing, the strategy gap will continue to erode performance and may eventually threaten the company’s very existence. But let’s say that leaders recognize the threat or opportunity the triggering event presents and initiate a change in strategy that, if executed well, will allow the company to thrive. In so doing, the strategy gap is closed, and all should be well with the world. But hold on, the culture that enabled the old strategy to be successfully executed hasn’t changed; there is a culture gap. The company’s culture has become a barrier the new strategy can’t overcome, resulting in culture drag. Until the culture changes and is aligned with the new strategy, we have a problem.

The existing culture continues to eat the new strategy for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

The complete book is available from Amazon - Click Here!

Culture Drag at a High-Tech Company

To explain the dynamics of culture drag, it can be helpful to use an example, and AVSC provides an excellent one. As you may recall, for several years, AVSC had successfully executed a go-to-market strategy that was effective because it was aligned with its cautious, risk-averse culture. The company focused its efforts on building its credibility as an innovator, providing leading-edge products to other technology companies. Among other things, it sponsored and hosted highly respected and well-attended think tanks and conferences, its researchers and engineers published countless peer-reviewed articles, and it rapidly grew its catalog of patents. Protecting the value of its intellectual property was of paramount importance, resulting in an extensive volume of legal policies, procedures, and processes. While the company had initiated litigation when necessary, it preferred to avoid the costs and risks this incurred.

But then something happened . . . a triggering event.

The Triggering Event

AVSC had missed its financial targets for three straight years. What happened? Their primary market, North American technology companies, was saturated, and they were struggling to find new customers. This was the triggering event. AVSC was forced to shift its focus to the EMEA and APAC markets. While the sales team had been trying to gain traction in these markets, they had yet to sign deals of any significance. Unless the company quickly remediated the situation, there was a very real risk that external market analysts would switch AVSC from a hold to sell rating. If this happened, investors would likely pull their money out of the company, which would be devastating.

The Strategy Gap

AVSC’s strategy, which had been successful in the North American market, was not working in EMEA or APAC. Specifically, while North American customers preferred to avoid litigation, their counterparts in EMEA and APAC had no such reluctance. In fact, they used litigation and, in some cases, the active involvement of government policymakers as an integral part of their negotiating strategy. This created a strategy gap, which essentially means the current strategy is not yielding the results required to achieve

the organization’s goals.

The New (Future) Strategy

To close the strategy gap, AVSC’s executives decided to use litigation when necessary to increase the pressure on potential customers who engaged in patent infringement. In addition, they decided to actively engage external lobbyists to persuade US officials to intervene on the company’s behalf in EMEA and APAC and advocate for trade policies that would put AVSC in a stronger position in these regions. The executives recognized that the work of the lobbyists was going to take time to yield results and concentrated their energy on litigation.

While there were several customer negotiations in progress, the executives agreed that it was prudent to test the new strategy before implementing it more widely. With this in mind, they selected a high-profile target in South Korea as their test case. The negotiations with this customer had been underway for over two years, in large part due to the customer’s delay tactics and AVSC’s desire to stay out of the courts. In addition to the obvious benefits of closing the deal and increasing revenue, the executives believed that testing the new strategy with this customer would provide insights that could be useful for future and current negotiations in the region. It would also send a message to other customers that negotiations were going to be different. AVSC was not only willing to litigate but would be aggressive in taking patent infringement cases to the courts.

Importantly, it would provide evidence as to whether the new strategy worked. This proof of concept was critical, as the executives felt the need to demonstrate to the financial market and the BOD that they were in control of the situation and AVSC was back on the

road to revenue growth and profitability. Confident they had landed on the right strategy, the executives quickly moved into action. Unfortunately, they didn’t consider the effect the company’s culture would have on strategy execution.

The Current Culture

To recap, AVSC’s culture was described by most executives and employees as risk-averse, cautious, and slow-moving. This was attributed in large part to its legal policies; however, the reality was that it went much deeper. For example, every decision of even moderate consequence required extensive data gathering and analysis. As a result, it was common for decisions to take months and require countless meetings, as well as massive amounts of investigation to answer questions and test every possible scenario. This also bred a fear of getting something wrong or making a mistake, which was evident in the behavior of people at every level. Instead of using their judgment and discretion, employees deferred to their manager, effectively shifting accountability off themselves.

Financial delegation of authority was also set at unusually low levels, which meant that spending decisions involving even moderate amounts of money, such as the purchase of a laptop computer for a new employee, required executive approval. Another example was

the inordinate amount of effort and time spent in preparing presentations. Heaven forbid someone put a semicolon where it shouldn’t be or used differently sized fonts in the titles. These are just a few examples. There were many, many more.

Boom—Culture Drag!

Despite the importance and urgency of the situation and the commitment the executive team made to aggressively pursue new business, the new strategy stalled. It couldn’t break through the barriers created by the company’s risk-averse culture. The culture gap was too big. In a nutshell, although legal supported the litigation strategy, they were not on board with reducing legal oversight. In fact, they doubled down on their current way of doing things, which included scrutinizing every document sent to a customer and actively participating in all customer meetings. Similarly, the executive team itself demanded an exhaustive amount of information regarding the litigation strategy and approach to negotiations, which led to weeks and months of churn. Instead of intentionally making the required changes to the culture to find an effective balance of risk and speed, behaviors didn’t change, and work continued to be done the way it had in the past.

This effectively put the kibosh on efforts to implement the new strategy. This is an important lesson! By not making the changes to behaviors, practices, and the organization system that were required to execute the new strategy, they doomed it to failure.

The complete book is available from Amazon - Click Here!

The New (Future) Culture

For AVSC’s new strategy to succeed, the company needed to be more collaborative, responsive, adaptable, flexible, agile, and risk-tolerant. At the same time, the nature of AVSC’s business meant that it was important to continue to protect the company from harm. This was not an “either/or” situation but rather one of “yes and.” In fact, there were many other aspects of its culture that served the company well and needed to be protected and even leveraged for the company to thrive.

This included the value the company placed on people, which was evident in formal and informal aspects of organizational life. For example, employees had access to best-in-class wellness, flexible work hours, and continuing education programs. AVSC invested heavily in diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, which was evident in the demographic makeup of its employees, starting at the executive level. On an informal level, executives made a point of getting to know people personally, embraced an open-door policy, and did a lot of little things like sending handwritten notes to employees on birthdays or when someone did something out of the ordinary. The list went on and on. In return, AVSC’s scores on its annual employee engagement survey were a benchmark for other companies in its industry. Despite the frustrations with slow decision-making and risk avoidance, employees were proud to be members of the company and wanted the opportunity to help it succeed.

Closing the Culture Gap

In an ideal world, every aspect of the way things get done in an organization—its culture—clearly supports the company’s strategy. Of course, changing every facet is hardly realistic. While a broad culture change strategy is needed, tackling everything at once would take a massive investment of resources and years. This was not an option at AVSC, nor is it possible in most organizations. AVSC needed to see immediate results in the EMEA and APAC markets. This was the compelling reason for change. Addressing other manifestations of its slow, risk-averse culture, such as the waste of resources spent preparing PowerPoint presentations and the bottlenecks caused by a lack of financial delegation of authority, was not going to solve the problem. Yes, these issues would need to be addressed if they would help build the momentum needed to change the culture, but this could wait. The priority was to close the culture gap, specifically as it was

manifesting in customer negotiations, and get deals signed.

AVSC opted to use an approach I developed called the CASPE culture change process (CASPE or CASPE process), which is described in detail in the following chapters. In summary, I facilitated three workshops with the executive team over a two-week period that resulted in the identification of a new customer test case and, importantly, clearly identified the changes to behaviors and practices required to drive

speed and agility while at the same time minimizing the risks to the company. This was followed by joint meetings with the sales, business development, and legal teams involved in the test case negotiation, during which they refined the approach and identified obstacles that the executives agreed to address. During these meetings, the joint team, including the executives, agreed to changes to roles and responsibilities, decision-making authorities, communication practices, processes, policies, and procedures. They also discussed and agreed on the behaviors they would do their best to emulate going forward, which included how they would handle conflicts, blaming, and other behaviors that had been evident in the past. Fast-forward six months and AVSC had its first signed deal in EMEA and APAC.

Of course, this is only the first step toward culture change. Over the next three years, AVSC systematically applied the CASPE process in other parts of the business, augmenting this with a broader employee engagement strategy that capitalized on the strengths of its current culture (see chapter twelve).

Lesson #20—Culture change is about finding the right balance.

One of the challenges I observed at AVSC was the tendency of people at all levels, including the executives, to view culture as “either/or.” Either the company could minimize risks or it could be decisive and agile. The reality was that, as the CEO suggested, AVSC needed balance to be successful. It needed to be aggressive while at the same time making smart decisions that would position the company well in future negotiations and litigation. This happens often in most organizations. An entrepreneurial company, like POM, that invests in

Lean Six Sigma or implements a new enterprise resource planning system like SAP is faced with the challenge of maintaining the existing

strengths of its culture while making changes most employees perceive as threatening to it. The result is resistance, as people default to an “either/or” mindset.

When approaching culture change, it is important people understand that you want to protect your existing strengths while at the same time finding a better balance in areas required to support strategy execution. Approaching conversations about the culture and need for change in this way can help to overcome the organization’s cultural defensive routines.

Lesson #21—Triggering events are a catalyst for change.

Broadly speaking, a triggering event refers to something that has happened or is happening that forces a reaction. These can be externally initiated, as with what happened at AVSC, but they can also be internally initiated. Mergers and acquisitions, changes in senior leaders, and the implementation of new enterprise-level technology or core business processes are just a few examples of internal triggering events. A merger or acquisition fits this definition because these are directly tied to a company’s growth strategy versus a direct response to something that has happened in the external environment.

External triggering events refer to things that have happened or are happening that affect the company and are outside the company’s control. These types of events are happening more and more frequently as companies struggle to meet the challenges of our increasingly volatile, unpredictable, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world. Consider for a moment the massive external changes that have happened in recent years and continue to happen. Technological advancements are occurring at an increasing rate.

Innovation in fields such as cloud computing, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, and virtualization are putting pressure on companies to keep pace or risk losing ground to more adventurous competitors. Technological change is also affecting customers’ buying patterns and preferences, as evident from the increase in consumer online purchases at the expense of brick-and-mortar sales. This has also played a major role in the rise of niche companies that use technology to provide a product or service better and faster than their less focused and bigger competitors. Geopolitical conflicts such as the US–China embargo and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have changed the parameters for doing business in these countries and others. Access to goods and materials, as well as customers, has been blocked or severely impeded, which has had a major negative impact on a significant number of companies.

Another example is the global COVID-19 pandemic that created massive disruption to the global supply chain, driving costs higher across a wide range of industries. Companies in several industries were forced to pivot or reinvent themselves or die. Take, for example, restaurants that, facing closure, changed their business model to offer takeout, home delivery, and even meal preparation packages to consumers. While this change may not last, other companies such as Spotify and Unilever made strategic changes that continue to yield results. As reported by Mauro Guillén in a 2020 Harvard Business Review article, Spotify offered “original content, in the form of podcasts. The platform saw artists and users upload more than 150,000 podcasts in just one month, and it has signed exclusive podcast deals with celebrities and started to curate playlists. The shift in strategy means that Spotify could become more of a tastemaker. At long last, the

company is doubling down on Netflix’s not-so-secret recipe for success in a business in which copyright owners enjoy healthy margins while pure-play streamers struggle to become profitable.” 14

These are just a few examples of the challenges, and occasional opportunities, created by changes in the external environment. Every company, regardless of industry or location, is affected to some extent by one or more of these events and others. It is the ability to recognize or, better yet, anticipate when this is happening and take appropriate action that determines if the organization survives or dies. Fortunately, there are companies that have not only been successful at pivoting and reinventing themselves but taken this to the next level, including Amazon, American Express, Corning, IBM, and Netflix. These companies have made reinvention a part of their culture and, in doing so, have developed a unique capability that gives them an advantage over their competitors.

Unfortunately, there are also lots of well-known stories of companies that failed to do this and are no longer in business, or if they are, they are a faint shadow of their former selves. 15 Blockbuster is a case in point. Multiple articles and case studies have been written over the years citing the company’s demise as the result of its inability to adapt its business model to the threat created by Netflix and on-demand streaming services. “At its peak in 2004, Blockbuster consisted of 9,094 stores and employed approximately 84,300 people.” As of 2023, it operates one store in Bend, Oregon, which is more of a curiosity and tourist destination than a retail operation. Kodak, which continued to bet on its successful photographic film products despite the emergence of digital technology, is another example. BlackBerry, which at one point had eighty-five million users, reportedly failed to innovate and rapidly lost ground to Apple, Samsung, and others. 17 The list is long. In most cases, leaders underestimated or discounted the changes that were happening. The result was a strategy gap that became so great that it was insurmountable.

Now, you may be thinking, Of course they failed. They didn’t understand the changes happening in the marketplace and external environment and adjust their strategy accordingly. What does it have to do with culture? This is a fair question, but as I will explain shortly, a company’s approach to strategic planning and its choice of strategy has a lot to do with culture, if not everything to do with it. That said, while it is rare to find a report about a company’s demise or a significant failure that references culture as a causative factor, there are a few exceptions. The most common occurs in reference to failed mergers and acquisitions such as AT&T’s 2016 acquisition of Time

Warner. 18 In this case, the differences in the cultures of the two companies resulted in a clash that contributed to a significant decline in AT&T’s financial performance. This was despite what appeared to be an ideal marriage of two companies with complementary businesses: Time Warner as a content developer with a valuable inventory of related assets and AT&T as a content distributor with a massive, established customer base. The other exception can be found in reports of companies that have been involved in scandals

or engaged in unethical actions that are usually attributed to the actions of senior leaders.

The Challenger space shuttle and Deepwater Horizon disasters are two of the most famous, but there are many others, including Enron, Barclays, Nortel, and Wells Fargo, the latter of which was described earlier in this book.

The complete book is available from Amazon - Click Here!

Lesson #22—Strategy gaps are linked to culture.

In chapter one, I made the point that culture is systemic in that it is embedded in and affects every aspect of an organization. This includes strategy. The beliefs and values of leaders influence how the company approaches strategic planning as well as its choice of strategy. For example, AVSC’s original strategy was a product of a formal, three-year planning process. This was a comprehensive and rigorous effort that culminated in a three-day off-site meeting of the executive team. The objective of the meeting was to recalibrate the company’s long-term goals and strategy and identify its priorities for the coming year. The meeting was jam-packed and fast-paced, taxing the energy of even the most well-rested executive. The process leading up to the meetings was also rigorous and exhaustive and involved extensive research and preparation completed by the company’s five-member corporate strategy office. The CSO summarized their findings in briefing documents that were sent to the executives well in advance of the meeting. These documents included information on market dynamics, external trends, and other developments that could be a threat or potential growth opportunity for the company. The

executives were expected to read the briefings carefully and use them to advance their thinking so they could make a meaningful contribution to discussions and decision-making. It was an unspoken rule that to arrive at the meeting without being fully prepared would incur the wrath of the executive vice president (EVP) of corporate strategy, and the CEO. This was something everyone wanted to avoid.

After the meeting, the CSO documented the decisions that had been made in the company’s formal strategic plan. When finalized, the strategic plan provided the focus for several of the company’s core business processes, including goal setting, performancemeasurement, resource allocation and management, and compensation.

In the years between strategic planning meetings, the executives reviewed the plan on an annual basis. The principal objectives of the annual meeting were to assess the progress made toward the company’s long-term goals and identify the priorities for the coming year. This also provided the opportunity to discuss emerging trends and developments in the external environment and adjust the long-term goals and strategic plan if needed. The latter only happened on very rare occasions, as any changes had to be approved by the company’s BOD. The BOD had made it clear they would only agree to a change to the company’s goals under exceptional circumstances.

In addition to concerns about a potential negative reaction by the financial market, they believed it was important to hold the executive team accountable, which meant not moving the goalposts. An unintended consequence of the BOD’s position was that the executives were reluctant to make decisions that deviated from the plan. If a new opportunity was identified, it would get tabled until the next annual strategy meeting. This meant the company failed to act on promising new opportunities, especially ones that required a quick response.

For example, the CSO once identified an opportunity to acquire a niche competitor. The team was very excited, as they had been monitoring the company for a few years in the hope that they could make a play to buy it. However, when they brought it to the executive team, they were told that a decision would have to wait until the next annual meeting. By the time this took place, the niche competitor was in the closing stages of an agreement with a competitor and the opportunity was lost. Leaders who support this type of structured, planful approach to strategic planning typically believe it provides the focus, alignment, and accountability required to succeed. To quote Ted Jackson of ClearPoint Strategy, “It’s a beautiful thing when an organization has hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of employees all pulling in the same direction to achieve shared goals. When that happens, there’s virtually no limit to what the business can accomplish.” 19 Leaders who favor this approach believe the extensive research and analysis that accompanies the planning process is essential, as it allows for better decisions and, importantly, mitigates risk. Furthermore, they tend to view the organization as an entity with finite resources. It is incumbent on them, as leaders, to utilize these valuable and scarce resources efficiently and effectively. While there may be occasions when this means making tough choices to not invest in an exciting idea or new opportunity, it is better to focus on a few priorities and successfully complete them than to take on too much and fail to execute. This same thought process applies to opportunities that arise during the year. Allocating resources to a new opportunity requires that people, money, and other scarce resources be taken away from existing priorities. This creates the risk that one or both initiatives will not be completed

or, if they are, not to the standard that is needed.

Contrast this with the strategic planning approach used by the leaders of another high-tech company that I worked with. In this company, a small team led by the EVP of corporate development (CD) constantly monitored the external environment to identify potential threats and opportunities. If something caught a team member’s attention, it was researched and, if it had merit, discussed with the rest of the team. The CD team would decide if the situation or idea should be shelved, monitored, or brought forward for discussion at the executive team’s monthly strategy meetings. These were carefully documented in the belief that even items that didn’t have merit at the time could be potential opportunities in the future. Items to be presented to the executive team were recorded in a “strategy roster” and briefing notes were prepared. The strategy roster was a dynamic, living document the CD team updated on a continual basis.

The CD team felt this was a more effective approach than a formal, multiyear planning process given the speed and extent of change that was happening in the industry. They believed that by the time a three-year plan was developed and executed, the world would have changed, and competitors would have left the company in their dust. The company’s leaders bought into the approach, sharing the belief that it would allow them to take preemptive action to address threats and take advantage of opportunities before their competitors. They also shared the belief that it was better to do something and fail than do nothing at all. They believed failures lead to better ideas and

all it takes is one great idea for the company to achieve a big win. As a result, they frequently approved strategic initiatives that had a slim chance of success. In fact, one of my favorite stories was told by a software engineer at the company—whom we will refer to as Samir.

Samir had been given the go-ahead to experiment with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in product development. He was given a small budget with the only ask being that he provide progress updates including demos to the engineering team at their regular Friday meetings. The team would evaluate his progress and decide whether there was merit in continuing his work. If the team decided to stop further work, he was expected to comply and share what he learned with other engineers to see if it would help spark an even better idea. He agreed. Everything was going smoothly until one Friday afternoon when the engineering team decided it didn’t make sense to continue with his project. While he was disappointed, he understood and accepted the decision.

A month later, Samir was invited to participate in one of the company’s quarterly innovation labs. The innovation labs were a big deal, as they provided an opportunity for the brightest minds in the company to get together with external thought leaders and talk about the future, share ideas, and experiment. One of the areas discussed was the future of AI and the opportunities it could create for the company. To say he was excited wouldbe an understatement. Even when telling me about this after the fact, Samir could barely contain himself, he was so delighted. He could hardly get his mind around the fact that his failure had opened the door to such an amazing opportunity. While AI had yet to become a strategic priority or initiative, it was on the strategy roster, so when the time was right, the company would be ready to act.

When I say that culture influences and informs strategy, this is what I mean. The way both high-tech companies approached strategic planning and the strategies they adopted can be clearly linked to the beliefs of the company’s leaders. These beliefs shaped the culture, which influenced the strategy. The lesson is twofold. First, if a company doesn’t identify and address a strategy gap, this may be the result of the culture and the beliefs of the company’s leaders. Second, leaders typically do not understand, because they don’t think about it, how their beliefs influence their choices and decisions and thereby influence strategy. These biases are, for most of us, accepted truths that

unconsciously shape our worldview and, therefore, our actions.

The complete book is available from Amazon - Click Here!

When Culture Is the Problem

Regardless of their approach, not that long ago, many companies could go years, if not decades, without changing their strategy. Even if a significant event happened in the external environment, these companies remained relatively unaffected. Large telecommunications companies like AT&T and Bell Canada are just two examples. However, the world has changed, and stability is now a luxury for most companies. In this new world, it is the companies that respond quickly and effectively to external change that have a significant competitive advantage.

This is why understanding culture drag is so important. It isn’t enough to recognize and take action to close a strategy gap; companies need to also change the culture, and quickly. If they don’t, they risk a disconnect between strategy and culture, resulting in culture drag, which interferes with strategy execution, negatively impacting the company’s performance and its ability to achieve its goals. In this way, the culture that contributed to past success becomes a serious business problem.

The first step in solving any problem is to understand what, precisely, the problem is. The model of culture-strategy alignment (diagram 5) provides a simple yet powerful tool to help leaders do exactly that. By working with the other leaders on your team to complete the model, you can achieve the shared understanding and commitment necessary to determine what changes are needed, if any. One option would be to adjust your strategy so it is consistent with your company’s current culture. Instead of changing the culture, you can focus on how to modify your strategy to take advantage of its strengths. If this is not an option, the only reasonable alternative is to change the culture

to support your strategy, which can be a daunting proposition.

As mentioned in previous chapters, the main reason culture change efforts fail to achieve their goals is because leaders delegate the responsibility to HR instead of actively owning the change effort. This is not because they don’t think it is important, nor is it because they don’t care. In my opinion, this happens because we, the culture experts, have been advocating the wrong approach. As Edgar Schein, a renowned professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management who is widely recognized for his groundbreaking work in the field of organizational culture, so eloquently stated, “Don’t focus on culture because it can be a bottomless pit.”

We can’t change culture by focusing on values, beliefs, and behaviors; we need to focus on the business problem caused by the culture. Values, beliefs, and behaviors are important, but we get to these by solving the business problem and, as part of this, asking, "What will we see people doing when the problem is solved?” By starting with a business problem that can only be solved by changing the culture, culture change is viewed as a critical business priority, elevating it to the same level of importance and urgency as other demands on leaders’ time and attention. However, while leaders have many skills and abilities, culture change is rarely one of them. For leaders to effectively lead culture change, they need a straightforward, results-oriented approach they can trust to deliver the outcomes needed. The approach must leverage the skills leaders already have, thereby giving them the confidence that, with a little help, they have what it takes to succeed.

The good news is that there is a solution, which is the CASPE culture change process. CASPE is a five-step process for solving culture problems that I developed and have successfully used in organizations for the past several years. It was sparked by the insights I gained from working with senior leaders wrestling with complex business problems. It is the culmination of decades spent searching for the answer to one question:

how can we achieve timely, meaningful, and sustainable culture change in organizations?

The complete book is available from Amazon - Click Here!

Dr. Nancie Evans

Dr. Nancie Evans is an author and co-founder and VP Client Solutions at CultureStrategyFit® Inc. specializing in the alignment of organizational culture and strategy. She has developed a unique set of leading-edge diagnostic tools and approaches that provide leaders with deep insights into the culture of their organizations, how it is supporting or getting in the way of strategy execution, as well as the levers that they can use to drive rapid culture change.

CULTURESTRATEGYFIT®

CultureStrategyFit® Inc. is a leading culture and executive leadership consulting firm conducting groundbreaking work in leveraging culture to drive strategy and performance. Its suite of culture surveys and culture alignment tools are used by market-leading organizations around the world.